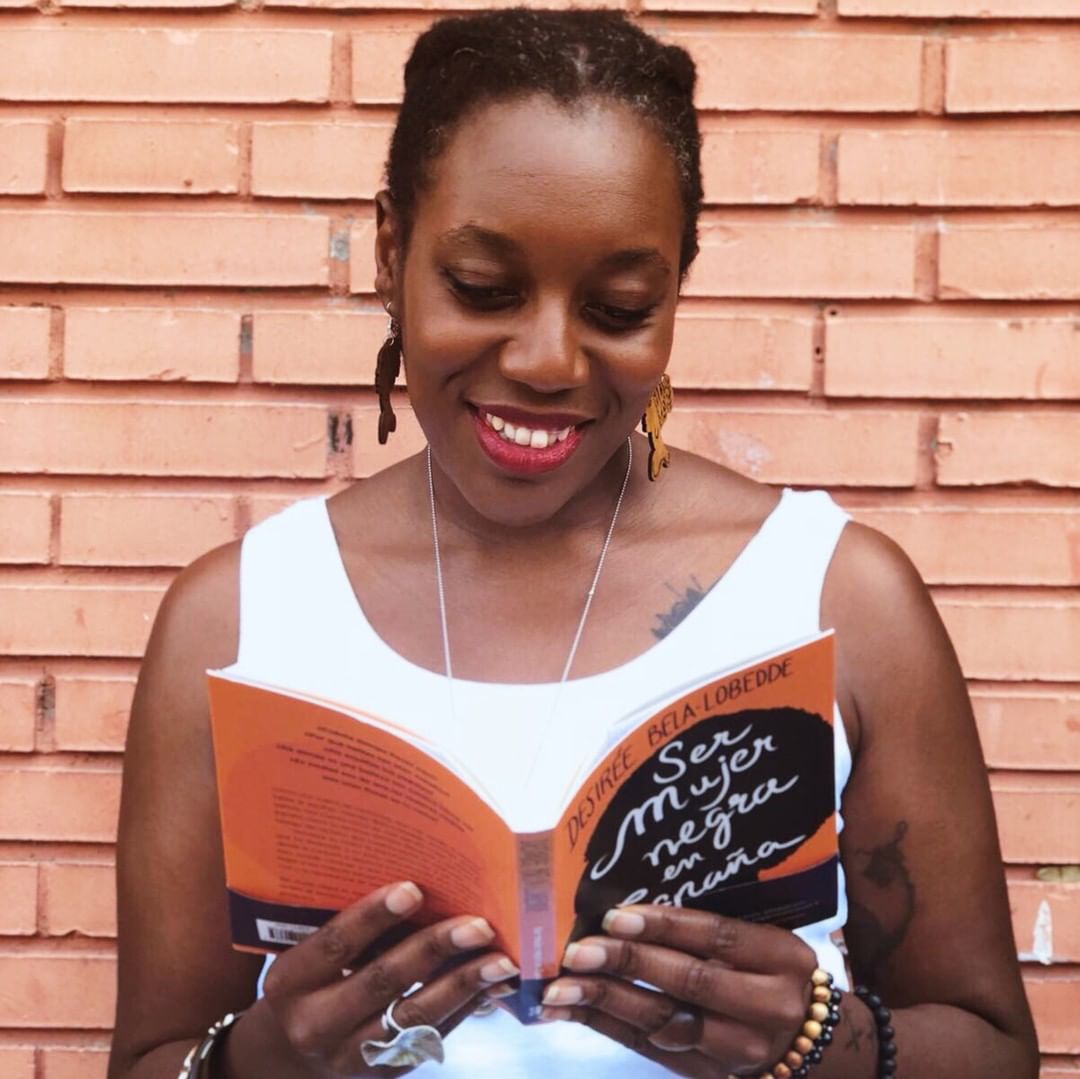

By and for black women by Desirée Bela-Lobedde

The Black Breastfeeding Week (BBW) was held from 25 to 31 August. This has been its seventh edition.

In the blog of LactApp, and in its social networks, there were a couple of publications talking about the need for this celebration, with the intention of making it visible. And, although it seems to me to be a necessary action in a medium dedicated to providing information on breastfeeding in general, I must say that the reactions of the readers made me uncomfortable.

I’m a lactation consultant, I’m a mother and I’m a black Spanish woman. And, from this position, I need to make some points about all those comments from women (white, I must say) who felt the need to make it clear that they did not understand the need to hold the BBW, so even though I am a breastfeeding consultant, this article, rather than focusing on breastfeeding, is going to focus on racism. Because yes, it is necessary to talk about the racism that leads many white women to question something that they don’t know if it is necessary or not, because it is far removed from their experience as women.

I know that now there will be people who have read this and have been shocked or offended. That’s okay. It’s a common reaction the first time someone points out racist behaviors when you think you don’t have them. But those behaviors are there, they’re very subtle, and they’re so ingrained and normalized that if we don’t point them out, they’re hard to detect. But there are other dynamics that are also impregnated with racism, with an undetected daily racism that permeates everything and breastfeeding is not impervious to it.

The BBW is a necessary movement to vindicate and, above all, to heal ancestral wounds. When white women complain that this World Black Breastfeeding Week exists, wanting to put us in the same bag with “all milk is milk” or “I don’t see colours”, they are invisibilizing and denying a whole history of institutionalized abuse that continues to have consequences today.

I am going to talk about some issues that explain the need for the BBW; but before going any further I would like to make something clear if you are going to continue reading: open your mind to what you are going to read here and try not to get defensive or question it right away. Some of these questions may be completely new to you, but that doesn’t mean that they’re a lie and that’s why you have to question them: it only implies that they’re new to you, but they’re the reality of many other women and mothers.

HEALTH

In the United States, studies have been published that report disparities in breastfeeding ratios and practices based on ethnicity and race. In fact, among women in minority communities, there is a lower rate of breastfeeding and lower attention to obstetric health, putting the pregnant bodies within these communities at greater risk. Therefore, there is a need to encourage breastfeeding among black mothers and to raise awareness among this group of mothers of the improvements in maternal and child health that result from this practice.

However, it is not just a question of breastfeeding: it is a question of differences in care for pregnancy and childbirth that lead to chilling differences. Thus, while the mortality rate for white women is 12.7 per 100,000, the mortality rate for black women is 43.5 per 100,000. We are talking about a mortality rate that is almost four times higher among black women. And for the mortality rate for babies in the first year of life, for white babies, the rate is 4.9 per 1,000 for white babies, and it goes up to 11.3 per 1,000 for black babies. That is, the mortality rate for black babies is slightly more than double that of white babies. If you’re interested, you can read more in this article, which also discusses what causes this gap.

In fact, racism is already present in the early days of gynecological practices, since one of the recognized fathers of gynecology, Dr. J. Marion Sims, performed vaginal and uterine surgeries without anesthesia on black women enslaved by the owners of the plantations. As far as is known, he performed these interventions on approximately thirteen black women, whom he intervened on several occasions.

REPRESENTATIVENESS

If you, who are reading to me, are a white person, it is possible that you have not considered the importance of having references that resemble you. After all, everyone you see in the media, in most professions and, ultimately, everywhere if you live in Europe, looks like you. My position, on the other hand, is totally different.

I see very few people who look like me. In the media, when black bodies appear, it is to talk about avalanches of immigrants or to talk about Africa from paternalism and condescension. And, in terms of professions, how many doctors, teachers, bus drivers or black supermarket clerks have you met? How many black women have you regularly interacted with in your life? And do you give breastfeeding advice? Have you met any? That’s why representativeness matters. Because black women have very few women referents because there is a systematic erasure of our presence. So it is important for me, as a mother and as a black woman, to see other black women breastfeeding or accompanying mothers in their upbringing. We need that support network so that we don’t feel alone.

HISTORY

I think here comes the most controversial issue of all: historical reparation. Colonization and slavery have sequels that last to the present day. The problem is that they only told us one side of the story, only one version of the story: that of the winners, and it was the black people.

During colonisation, Europeans arrived on the coasts of Africa with slave ships in which they abducted millions of African people in order to take them to work forcibly on the American continent and also to the slave markets and human zoos in Europe. Let me remind you that slavery gave white people the right of ownership over black people. Slavers could do what they wanted with the people they enslaved. And, within that doing what they wanted, black women got hurt.

Black women enslaved were systematically raped by slaveowners. If they became pregnant, they gave birth to these babies (the fruits of non-consensual sexual intercourse), who were separated from their mothers at a very young age and sold to other plantations. If, in addition, in the slave-owner’s house, his wife had a baby, the black woman had to leave her own baby to nurse that white baby.

There is a very unknown story and a very deep pain behind black maternity wards. There is damage to be repaired from the moment that black women (in the United States) have been able to take responsibility for their sons and daughters for less than two centuries. And there is a general stigma that weighs on black women and our child-rearing practices, which makes us infantilized and exotic since colonization.

In conclusion, the celebration of Black Breastfeeding Week is an exclusive need of black women, because the problem is totally different from the problems of white women. We need to recover spaces of visibilization, also as for maternity, lactation and upbringing in a society that tends to whiten and invisibilize the questions related to non-white bodies.

In the end, as Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw says, “when there’s no name for a problem, you can’t see that problem. And if you can’t see it, you can hardly solve it. Making Black Breastfeeding Week visible is an action driven by black women and for black women. It is an activity that helps us to make ourselves visible, to recognize ourselves, to support ourselves and to look for our own resources in order to put an end to a real, current problem that, fortunately, has a solution.

Follow Desirée Bela-Lobedde

Blog: https://www.desireebela.com/

Libro “Ser mujer negra en España”